The Simple Gift of Light #9

Comfort. Work. Safety. Three of our lighting zones have names that invoke ideas that most of us want: few would say “no comfort, please.” The Glare Zone, however, has a much different ring to it. Perhaps every human eye should come with a READ ME FIRST! warning, every home that has overhead big lights a sign that says, “According to the State of California, overhead lighting has been shown to….”

If light can help us wake gently, move with energy, relax easily, and rest deeply, then light can probably hurt us, too. I suspect you know this already: driving westward into the setting sun can hurt, facing bright headlights can temporarily blind the nighttime dog walker. Outside the home there is often little we can do to mitigate the effects, like averting our eyes from the sudden brightness. We cannot predict when a car will approach in the oncoming lane, nor can we reach into the other car and dim their headlights.

Inside the home is different.

We have much more control over light in our homes, our own personal environments, and the choices we make can impact our enjoyment of life on a daily and nightly basis. While I prefer to focus on the positive aspects of light, there is one zone that keeps my focus on the negative effects of bad lighting. We can wake with a jolt, strain our eyes while working, try to relax under harsh lighting, and struggle to sleep after drinking too much light at night. Most of the light that hurts us comes from above, and above our eyes is a unique are of vision highly sensitive to light.

The Glare Zone can be a scary place, but it can also be a beautiful place.

I made up the terms Comfort Zone, Safety Zone, Work Zone, and Glare Zone in an attempt to take a lot of scientific and technical information and make it understandable, and I did not go through this exercise just to make others happy. I, too, need constant reminders of what light goes where, of what light can do, and of what light to avoid, and the simple Zones keep me on track. I can look at a room and simply ask myself, “is there likely to be harsh light in the Glare Zone?” and the answers become easy and actionable.

These made-up terms, however, are not just my opinion, but rather a combination of science, biology, sociology, and technology boiled into something useful. The Glare Zone is real, but in textbooks it is called “peripheral vision.”

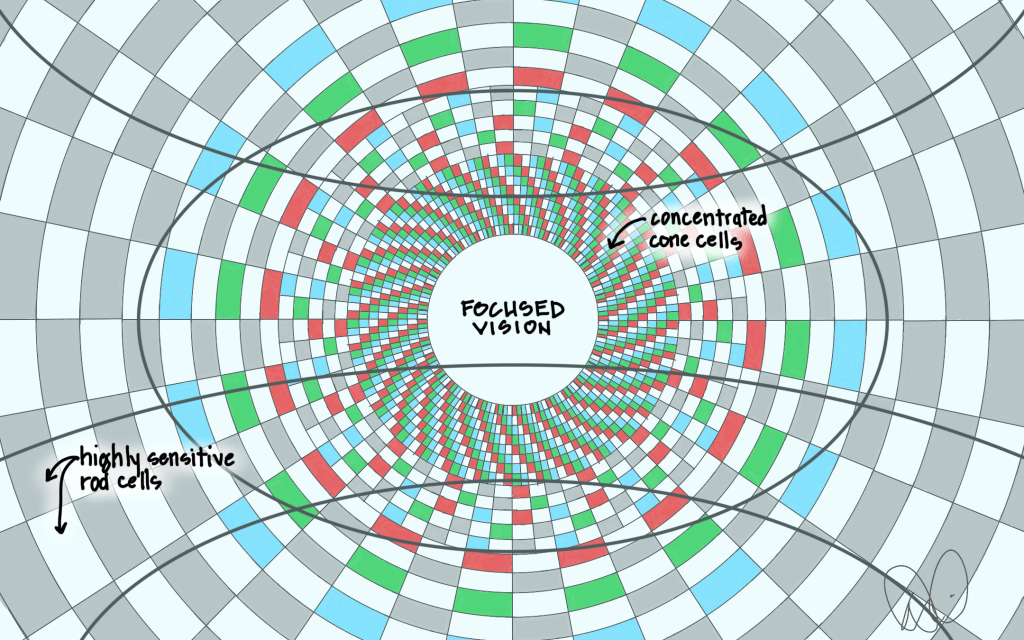

The retina in our eye, the layer of light-sensing cells along the back wall of our eyeball, is hit with focused light that travels through our cornea (lens) and pupil (opening). There are millions of rod cells and cone cells in each retina, each with a purpose. Cone cells, of which there are roughly six million in each eye, are the cells we use to discern color and roughly correspond to red, green, and blue receptors. They are concentrated in our near field of vision and, at the center (technically the fovea, shown above as the white circle labeled “focused vision”) cones are packed so tightly to help us see clearly that there are no rods at all.

Rods, represented by the gray and white rectangles, are colorblind but are far more sensitive to light. They far outnumber the color-sensing cone cells: a single human eye contains around one hundred million rod cells or more than ten times the cone cells.

Think about that for a moment. All day long we see things in color. Our computer screens, the sky, the siding on the house across the street, the color of our walls, the food on our plates. If the important stuff is all seen in color, why do we have so many rod cells that see in black and white?

Rod cells become critically important at night, when historically humans had very little light available. When we walk through a forest at midnight, we see little to no color but rather black and gray shapes. Inside our homes, however, we may only experience this level of darkness deep in the night when all the lights in the home are off.

Rod cells, concentrated as they are in our peripheral vision, help us see movement “out of the corner of our eye.” Eyes have no corners, but the highly sensitive rod cells in our peripheral vision pick up the slight change in light when something moves.

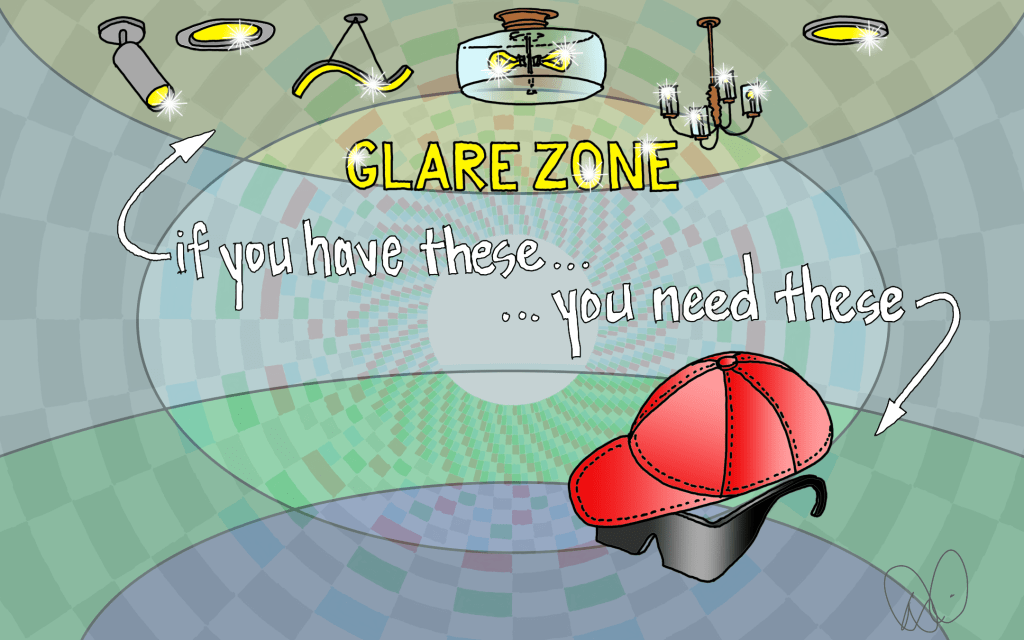

These same rod cells make us hate overhead lighting.

The Glare Zone is shown above in pale yellow and is typically the ceiling of our homes. Technically, the Glare Zone goes all around the perimeter (periphery) of our eyes, but we seldom put chandeliers, downlights, wafer lights, and other Big Lights on the walls or floor. Yes, that would be a problem, but most of the glare in our lives comes from above.

Did an adult ever tell you that it is rude to wear a hat indoors? I do not know what social rule maker set that particular convention but I do no this: with the brightness of today’s overhead lighting, we should all consider wearing hats indoors. They are designed to shield our eyes from glare, and glare is precisely what most overhead lighting creates in abundance.

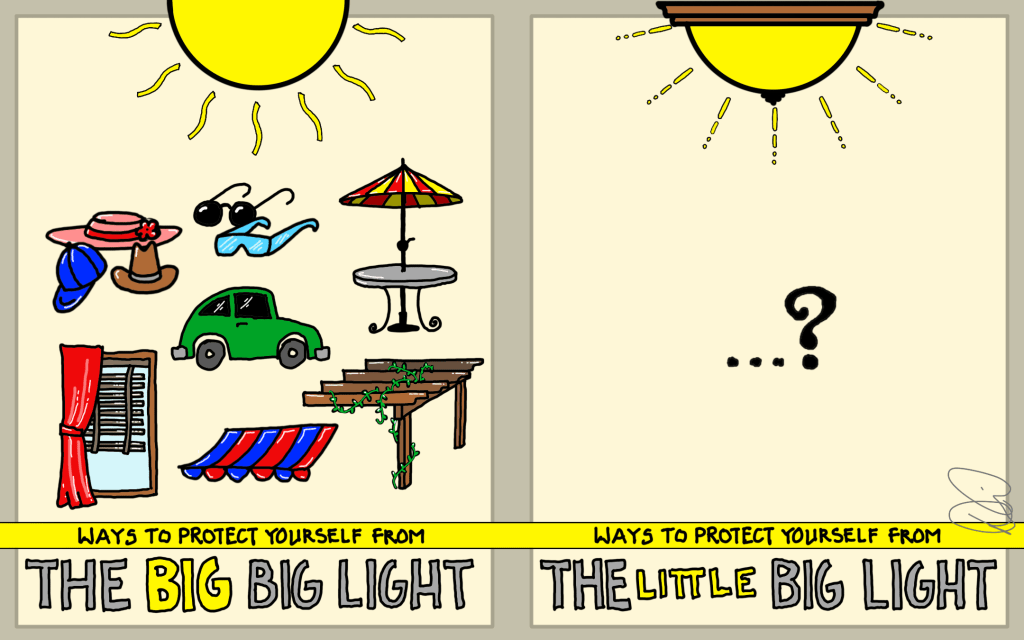

On a sunny summer day, the sun can be so intense that looking directly at it burns an image in our retina – and can do greater damage if we linger too long. We cannot dim the sun, we cannot turn it off, we cannot add a shade to it, so over time we have developed a myriad of ways to be more comfortable outdoors.

If you have ever sought the protection of a patio umbrella or an awning, you might consider putting an umbrella over your dining table to block out the chandelier.

If you have ever worn sunglasses, you can get the same results inside by adding dimmers to all your lighting.

If you have tinted windows, or curtains, blinds, or shades, you know that too much light can be uncomfortable.

Sadly, inside our homes, we hang up our hats, take off our sunglasses, and leave the other big-light-blocking solutions outside. That leaves us subconsciously suffering from glare every night.

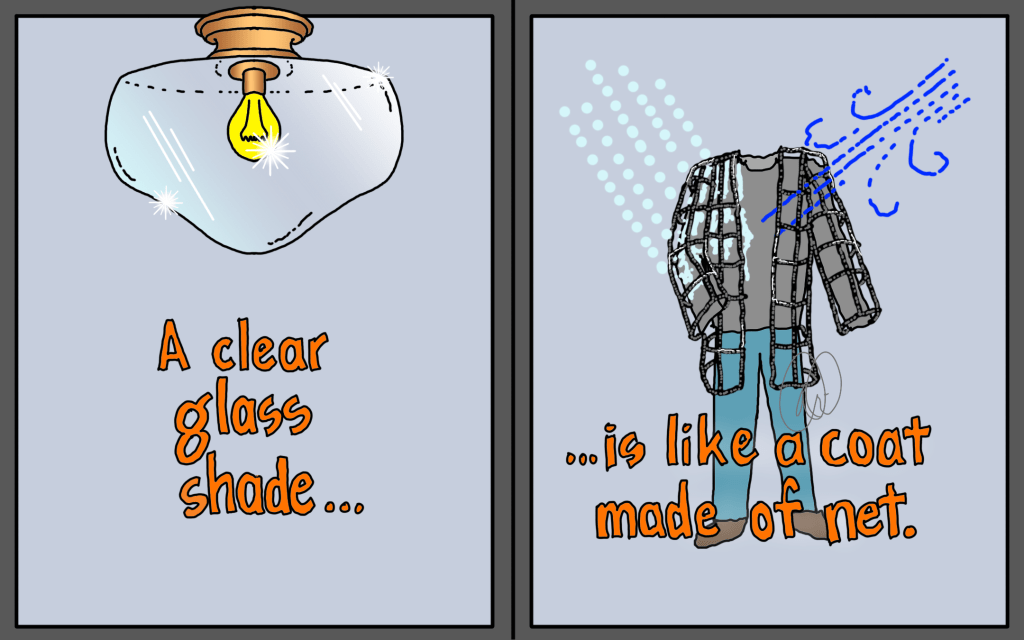

We have messed up our Glare Zone so badly that the one eye-saving technique we have, soft fabric or frosted glass shades, went out of “style” and was replaced by clear glass shades. Shade means “less light,” and clear glass technically shades nothing. This might have been okay when our light sources were candles and oil lamps, but today’s electric lighting is exponentially brighter and our eyes are overwhelmed with glare.

Clear glass does not shade anything. A coat made of net will not protect you from rain or wind, even if it is all the rage on the Paris runway. Light fixtures, especially decorative fixtures like chandeliers and wall sconces, are subject to the fickle nature of fashion. Don’t be fooled.

So what should we do to protect our eyes from harsh light in the Glare Zone? Avoid Big Lights, unshaded lights, and recessed downlights that point at your faces. Instead, consider lighting the Comfort Zone, Work Zone, and Safety Zones with specific, shielded lighting. The best light for the Glare Zone is no light.

Getting our Glare Zone right, protecting the rods in our retina from harsh lighting, often means using techniques that did not exist one hundred years ago when many lighting fashions were set. In other words, if you want a Glare Zone that does not hurt, you will need to consider “modern” lighting techniques.

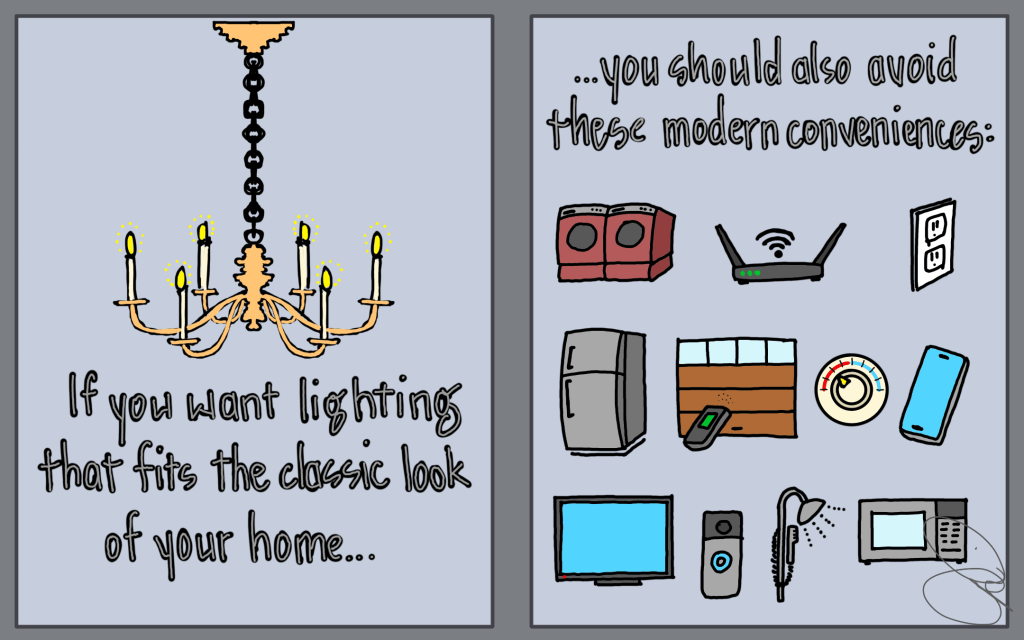

In my own work as a lighting consultant, I regularly hear from clients who think some of my proposed solutions are too modern. “Can’t we just have a chandelier? I don’t think those other kinds of light are appropriate for the style of our house.”

Perhaps indirect cove lighting was not around when your style of house was invented. But likely neither were washing machines, WiFi, garage door openers, or indoor plumbing.

If you make exceptions for countless modern conveniences that make your life more comfortable, more enjoyable, more livable, why resist the one modern convenience that can make every single moment better?

Protect your Glare Zone. Your eyes will thank you.

Leave a comment