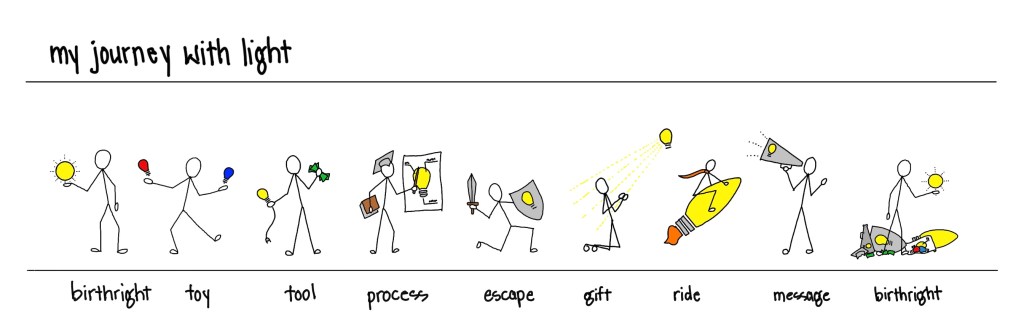

Light became a tool when I landed my first job in architectural lighting following graduate school, but my journey did not continue on a tidy linear path. I learned quite a bit from my employers and coworkers and enjoyed the excitement of working on high-profile projects in downtown Chicago and beyond. Unfortunately, I was also young and headstrong, convinced of my own invincibility and frustrated with my employer’s refusal to acknowledge that I was God’s gift to lighting design.

So I quit my job, vowing to start my own business, hire all my former coworkers, and show my bosses how it should be done. I was, in the words of Harry Rex in A Time to Kill, a “presumptuous little sh*t.” It took me the better part of ten years to own my mistakes, apologize to my former employers, and grow into a mature professional.

In the meantime, I needed money to pay the bills while I started my company, and I thought a teaching job would be the perfect gig. University professors don’t really work, right? A couple of hours of class per week, long summer vacations, a month at Christmas, weeks off for fall and spring breaks…if you sense a thread of naivety, you would be correct. One of the pitfalls of being a pseudo-pioneer is that we tend to have more hope for the future than practical knowledge of what lies ahead.

As fate would have it, a teaching job opened at the university where I had recently completed my Master of Fine Arts in theatrical lighting design. I won the job and went to work as an academic, a tangent that would occupy the better part of the next twelve years. It was on campus that I began to see lighting design as a process.

Let’s step back for a minute and address whether a process is needed for residential clients. Why do I feel such a strong need to simplify, codify, and explain the lighting design process?

Lighting design is complex and evolving field that attempts to combine the tremendous technological advances of the past twenty years, the deep discoveries of light and human wellbeing, architecture, construction, and design into a single drawing that says, “put this kind of light here.” Light, in this illustration, is a mountain that must be climbed. It is a long, hard climb for lighting designers to reach the top of the mountain (if the summit is ever really reached at all, as the mountain continues to grow), and even more intimidating for homeowners who must free solo climb in a very short amount of time. From the top, lighting designers shout “hey, this is going to be worth it, follow me!” A simplified process might make this approach a little easier.

And light is not the only mountain a homeowner must climb. When building a new home, clients face a myriad of decisions that cost money and require particular expertise. Some of these decisions they expect, like how to choose an architect or builder, where to build, what size the home should be, or how many bedrooms they need.

Once involved in the project, perhaps after summiting the mountain of known decisions, homeowners are faced with the unexpected climb of decisions they did not even know existed when they started the project. Do they want double or triple-pane windows? Low-E coatings? Ceramic tile or stone in the lower-level powder room? Wood-burning fireplace, gas, or hybrid? What carpet would they like in the third bedroom? Perhaps a little weary already from the first mountain, our homeowner heroes dig into their reserves (both financially and physically) and labor up the second mountain…

…only to find a third mountain beyond. Some will never climb the light mountain; most will never even know it exists. They will stop before the reach the finish line, stop before they get the most out of all those decisions. They picked carpet and tile and paint and curtains, but how will those look after sunset? Burdened with decision fatigue and way beyond their anticipated budget, there simply is not energy to climb another mountain.

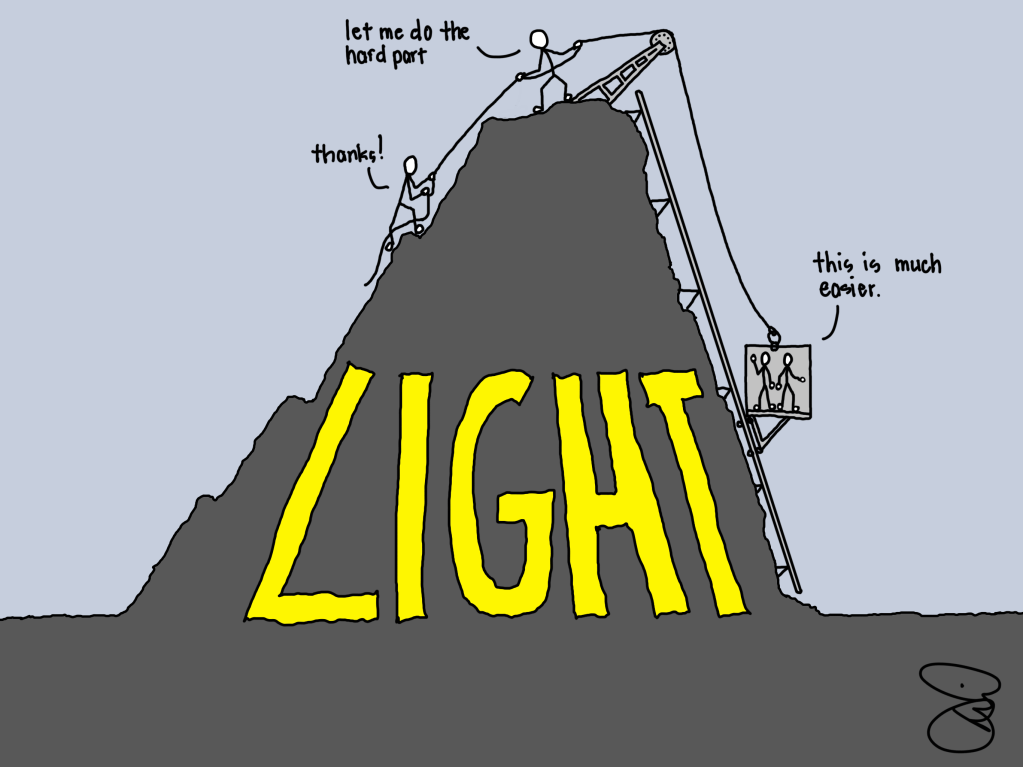

That’s where process comes in. By simplifying the science, technology, and craft of lighting design into a discernible process, we create a funicular lift for clients to ascend the light mountain. On the backside of the mountain, the same process makes it easier for aspiring lighting designers to climb to the peak. The lighting designer has more work to do to build and maintain these lifts and ropes, but the benefit to others can be enormous.

I started this process as a university professor, but I first had to learn what I was going to teach. I geeked out, carried around a copy of the IES Ready Reference, had three aluminum briefcases of light bulbs (yes, for real), and studiously followed the seven step process for theatrical lighting found in the textbooks I inherited from previous faculty.

Then I attempted to pass the information along to a bunch of hung-over 19-year-olds in a 9am class. I do not know if any of my students learned very much from me in those early years.

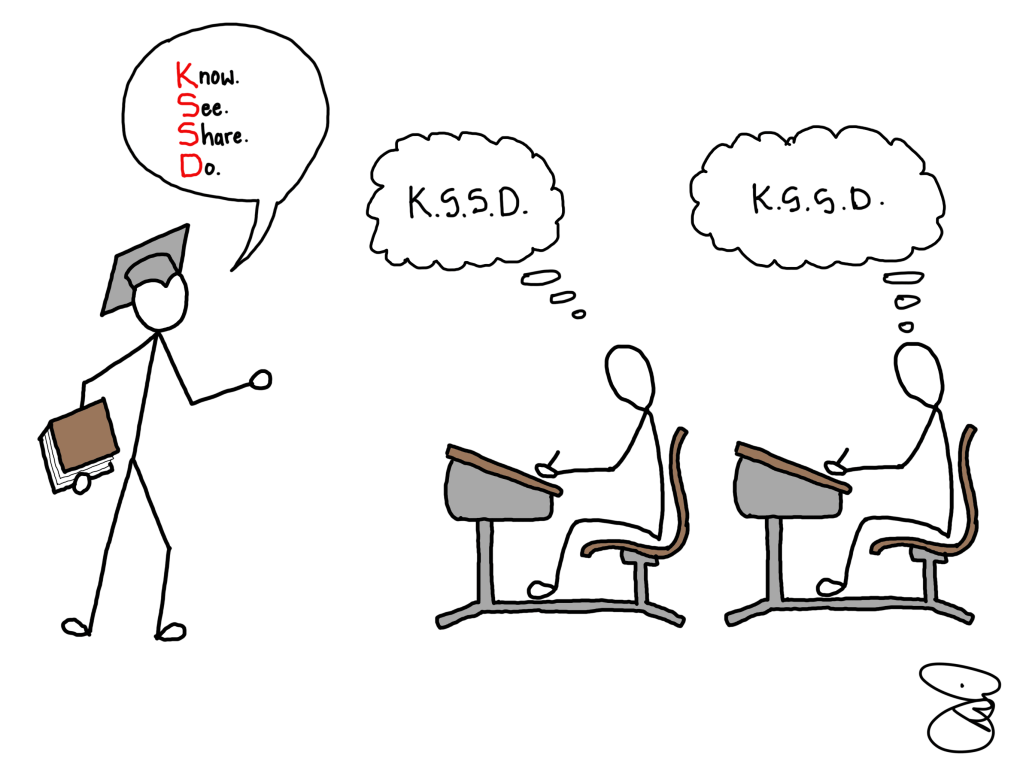

Somewhere along the way my understanding of light began to shift. It took me a few years, but I eventually realized that the textbook process was not how I approached design…and was not very easy or fun to teach. I toyed around with different strategies and eventually landed on a four-step process for theatrical lighting design: know the play, see the possibilities, share the concepts, and do the work. Each step had substeps, patiently systematized and simplified over a half dozen years until I had a process that was (I believed) easier to teach, easier to learn, and easier to use. A few years in, a student asked me when I came up with “kissed” as a process. I hadn’t even noticed that KSSD had an easy-to-remember name.

Fast forward twenty years and I find myself still drawing on this process of discovery, simplification, and sharing. My entire Light Can Help Us series this year is an opportunity for me to both share my process for architectural lighting and continue to refine it. Each improvement makes the mountain easier to climb for myself, my team, and my clients.

Light as a Process enables progress and facilitates communication. Eventually, light would even serve as an escape route for my exit from academia….

Read more of my Finding the Gift series HERE.

Sorry, you lost me at those 5 infamous words “When building a new home”. Considering all the multi-million of homes built to date (including “spec” homes that have no owner input), everyone else is left out. Seems most architects, building scientists, and general contractors are of the same mindset – ignore the vast majority to concentrate on the extremely few (in this case, new builds with specialized demands like no 4 cans and a fan in the bedrooms). Good lighting (like good/useful/site-specific building, good weather/moisture/air/thermal barriers, good energy management) should apply to ALL houses, not just new/custom/unusual builds. And the initial assumption by engineers/designers should be “this is a retrofit situation” to drive replicatable solutions.

LikeLike

Yep, this post is definitely aimed at those with the resources to build a custom or semi-custom home. I have found that building a simplified process for lighting opens up the potential of helping those at a wider variety of incomes, but I agree that good lighting should apply to ALL houses (see last week’s light + justice post, for further discussion on that topic).

LikeLike